Why Housing Breaks People's Brains: A Visual Guide

Housing shortages are uniquely counterintuitive. These images show why.

Housing shortages are causing sky-high housing costs, and economists widely agree building more housing is the solution.

Yet research finds many people don’t get why building more housing helps lower costs—even when they want to and understand how it works with other goods. Jerusalem Demsas summed up the phenomenon: “The Housing Crisis is Breaking People’s Brains.”

Many theories for this have been proposed: a desire to increase one’s property values, racism, change aversion. All surely contribute, but none fully explain the variety of people—renters, homeowners, black, white, rich, poor—who show it.

Here’s an alternative explanation:

Housing shortages look very different than other shortages of other goods, and are fundamentally counterintuitive to visualize.

Let’s take a recent example of a shortage: that of toilet paper during Covid. Here is a typical visual:

In this case, it’s intuitive there’s something wrong because the supply of the good is missing from where you expect to find it.

Now let’s look at a neighborhood with a housing shortage.

Nothing is obviously wrong.

Housing shortages look different because when housing is rented or sold it doesn’t go anywhere, it remains in public.

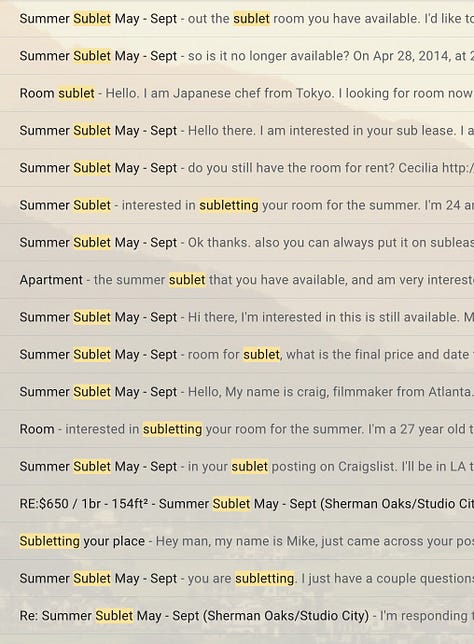

Also, most people looking for housing aren’t in public where we can see them. They’re at home searching online on Craigslist or Apartments.com.

With housing, demand is largely invisible, while supply is not just visible—it appears to be all around us. This makes the reality that demand is greater than supply counterintuitive.

A homeowner walking through their neighborhood might think “how could there be a housing shortage? I see housing everywhere. In fact, there’s more than there used to be since that apartment went up 5 years ago!”

Humans are extremely visual thinkers. “More than 50 percent of the cortex, the surface of the brain, is devoted to processing visual information,” points out Williams, a Professor of Medical Optics at the University of Rochester. “Understanding how vision works may be a key to understanding how the brain as a whole works.”

The good news: we can use visuals to explain the housing shortage, and when people see them they often understand it better.

Here is the same neighborhood with the housing shortage when one available apartment has a public showing.

This video captures both supply and demand. It makes it clearer what the problem is, and the caption draws correct conclusion: huge demand relative to supply is enabling landlords to raise prices. And there are plenty more to be found.

In her article Demsas notes that the answer is obvious when you see vivid images of people lined around the block.

But could the problem be that those images are not what people usually think of when considering housing reforms?

Part 2: The Effects of New Housing Are Hard to Visualize

Let’s play a game.

Pretend you are in an expensive city (you may not even have to pretend!).

Imagine a new proposal will allow ten story apartment buildings in neighborhoods that currently are just houses.

Take a second to think of the impact.

What did you think of?

I’m going to guess that you visualized an apartment building in a neighborhood.

In any case, that’s how housing bills and projects are typically presented: a picture of a big shiny new building like this one.

Look at this. Does it feel like it should lower rents in the neighborhood?

It looks expensive. Expensive things cost a lot. People who can afford expensive things live in them.

So it’s not surprising that when proposed as a solution, people who want to lower costs have questions like:

“What is this going to rent for?”

“Is it affordable enough?”

“Who’s it for?”

The problem that we want to solve is high housing costs across the region. But this doesn’t seem like a solution to that: it looks like high cost housing!

The construction of new buildings in areas with rising housing costs also often leads people to get the causality backwards—assuming that the rising housing costs must be a result of new construction rather than a response to it.

The effects of initial visual impressions are also very psychologically strong. They are extraordinarily hard to shift even after better information becomes available, which could explain why people who initially perceive new buildings as too expensive can remain skeptical even if it turns out they are actually low-income housing.

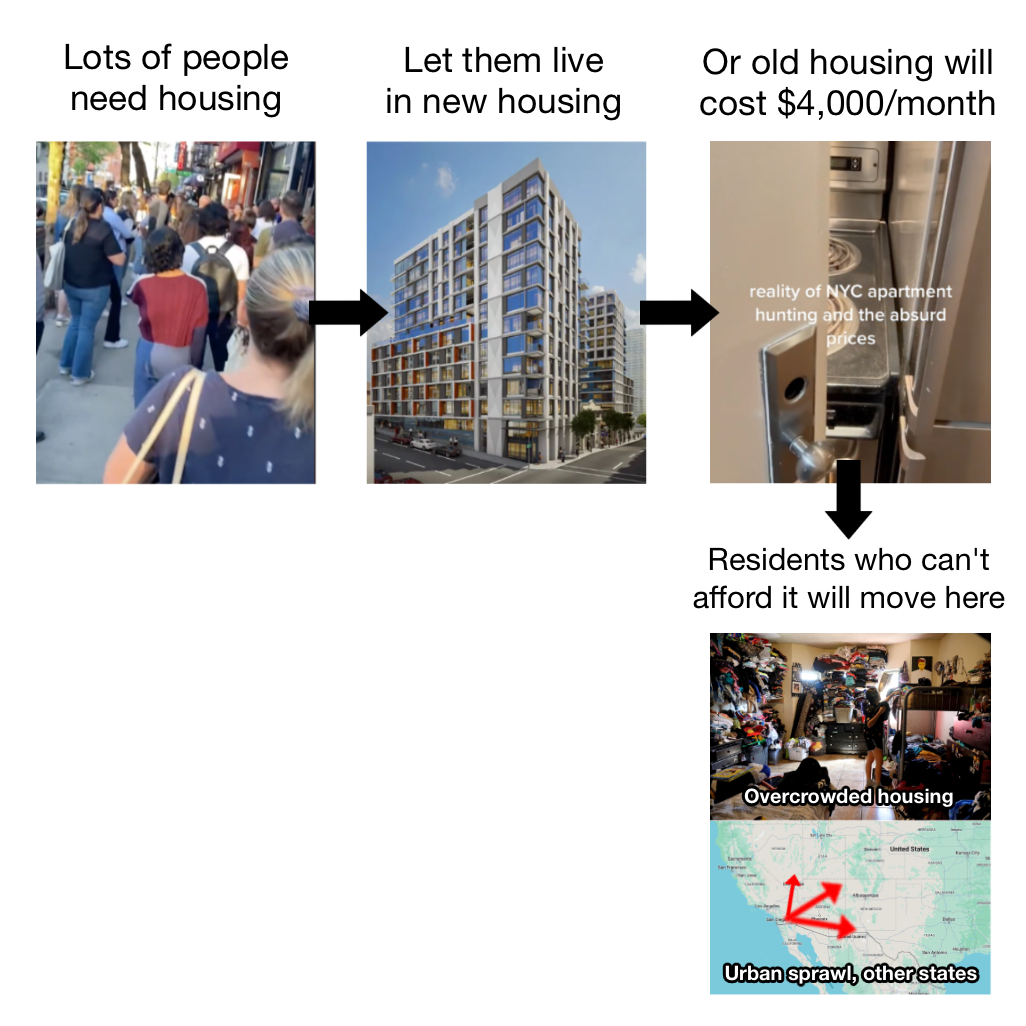

If we start with a picture of the problem, explaining the solution is simpler.

Way simpler than arguing about abstract economics.

But there’s another problem. When we center the discussion around visuals of a new building or buildings, discussions of affordability are often confined to just the new buildings being proposed.

This overlooks that housing affordability is a problem in the far larger number of existing apartments.

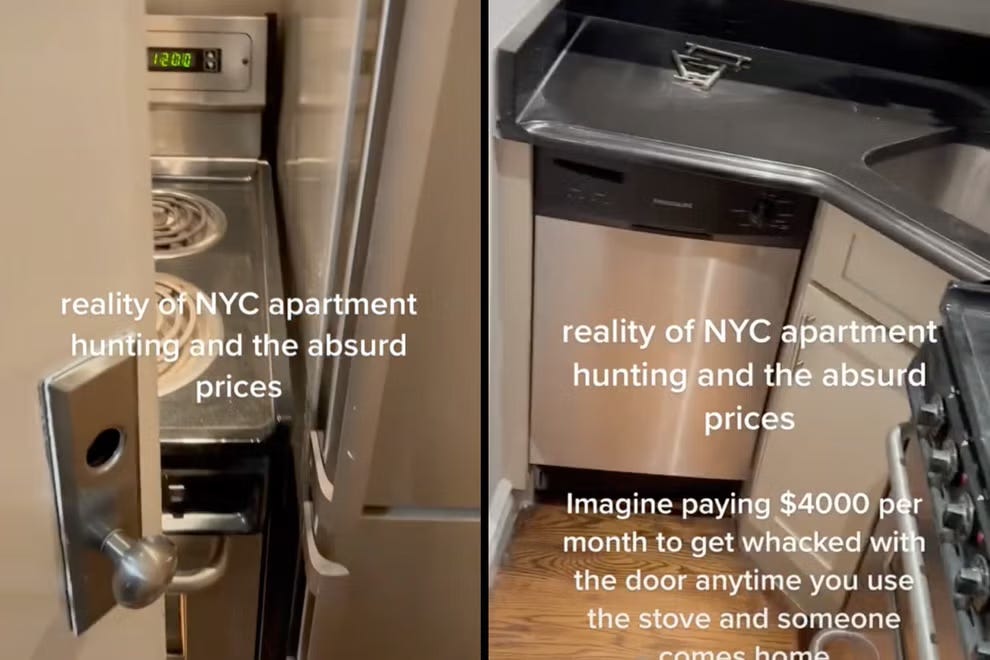

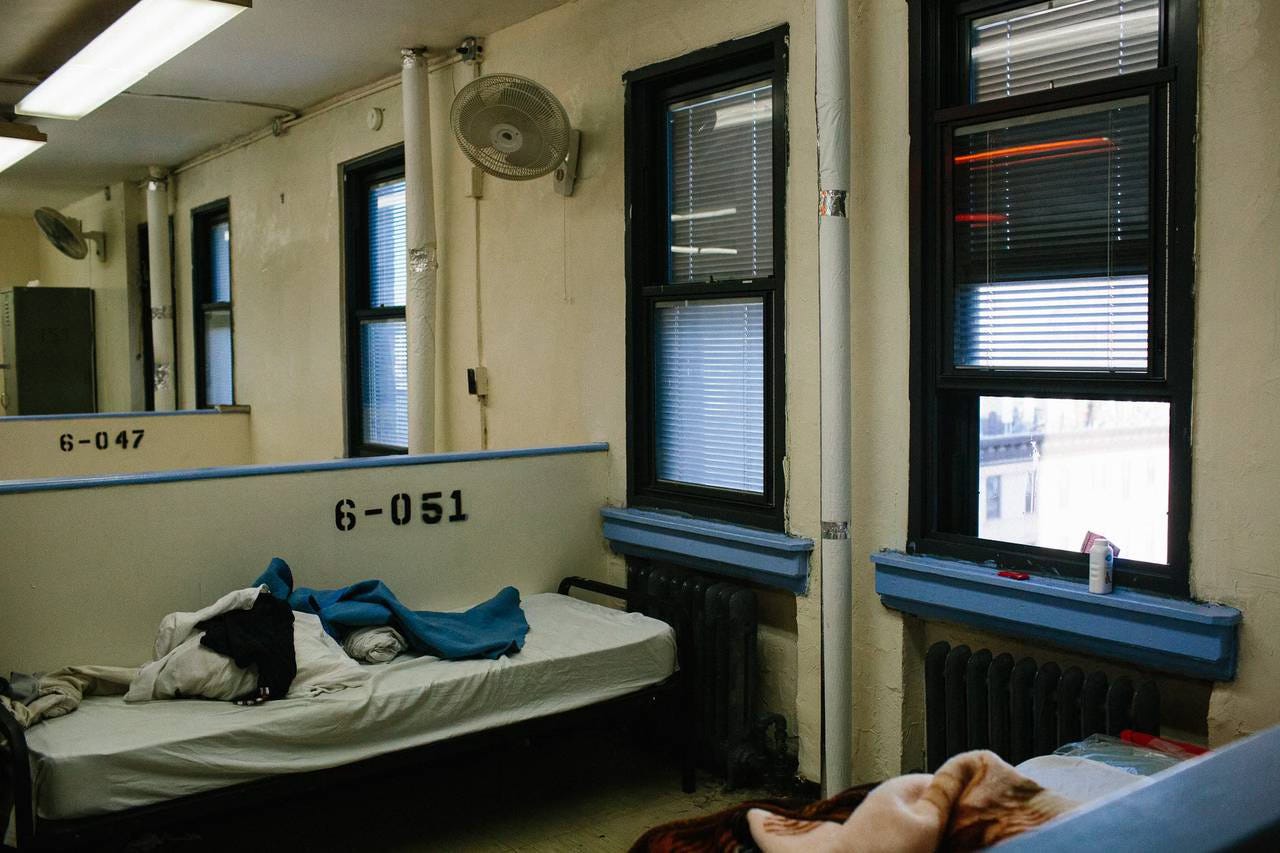

A key visual to show this: Old, shabby apartments that are now expensive.

Here’s a tiny Manhattan apartment going for $4,000 a month whose front door doesn’t open all the way because it’s blocked by an oven.

The visual of a crappy yet expensive apartment shows demonstrates that apartments aren’t expensive because they’re “luxury,” but because they’re scarce.

This is counterintuitive when looking at picture of a shiny, new, expensive-looking apartment building: the natural inclination is to attribute the high cost to its visible appearance rather than the invisible scarcity of housing in the neighborhood.

Let’s add this to the previous story.

This also explains gentrification—how old, inexpensive housing rises in price and working-class communities are pushed out.

Pundits often blame visual things like fonts signs use as causes of gentrification, as though that is the primary driver of housing cost rather than only a small amount of housing being available for a large amount of people who want it.

When we correctly diagnose the problem as a housing shortage, other bad outcomes make a lot more sense:

People overcrowd the few available apartments to split the rent between more people—causing thousands of deaths during the pandemic.

People commute from ever-more distant areas, exacerbating traffic and emissions.

Working class people moving to states like Texas—flouting blue cities’ commitments to them (not to mention causing labor shortages and inflation).

Let’s add these to the picture.

But that’s not all: when you combine expensive, scarce housing with personal misfortune—disabilities, loss of family, domestic violence, etc—people are much more likely to become homeless.

In a city like NYC with a right to shelter, that probably means a homeless shelter.

In a city like LA, with only 33% of the shelter beds needed for everyone experiencing homelessness, people are more likely to end up living in their cars or on the street.

Let’s add these.

Side note: an important factor here is rent control. With rent control, existing residents have more ability to remain in their homes rather than being priced out. However, it only slows the increases and—as the diagram shows—doesn’t address the root issue of unmet demand. This means it doesn’t provide a long-term answer for where the children of those residents live or new working-class migrants to the city can go. Rent control laws can also impact the creation of new housing, but that’s a topic for another day.

Why Homelessness Breaks People’s Brains

Study after study has shown rates of homelessness are directly linked to shortages of homes. But as with housing, many people struggle to accept that.

As an exercise, let’s consider a normal person getting asked about the housing crisis and visualizing the problem and solution.

If you are only thinking of the two commonly visible pieces—street homelessness and new buildings—it’s not obvious how they connect.

People are most likely to attribute high rates of homelessness to the visible personal symptoms of the people they see on the street—despite extensive research finding that even in areas where things like substance abuse or mental health issues are more common, the cost and scarcity of housing is what determines whether an area has high rates of people without housing.

So you get the questions that everyone who advocates for more housing are familiar with.

Are more brand new buildings really going to help the homeless?

Is lack of a brand new building really the reason a homeless person I saw is homeless?

Do new buildings cause homelessness?

The Mistake Politicians Make

Politicians can make the same mistakes with visualizations, but they are exacerbated by their tendency to defer to long-term residents in areas as local experts on housing issues. They often talk about “what they’re hearing on the doorstep” - but that doorstep is of someone who has a home.

Long-term residents likely haven’t looked for housing in the neighborhood for years and aren’t familiar with changes in the balance of supply and demand. To them, it’s mysterious why there should be a housing shortage. Not only is all the housing still there, there may even be more housing there used to be!

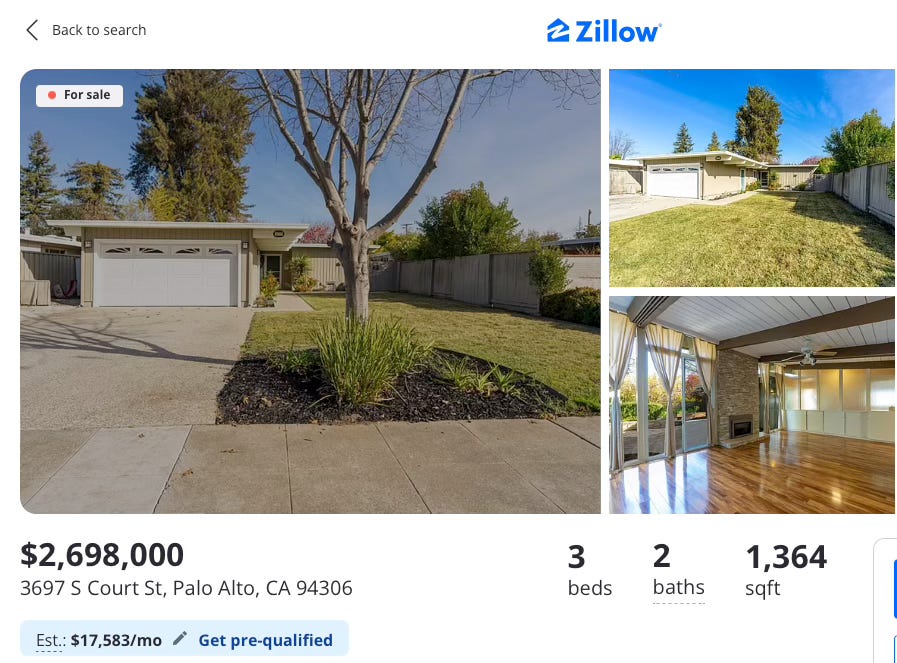

You similarly may hear them lamenting that nobody builds “starter homes” for their kids like they did in previous generations—while overlooking that the exact same starter homes now cost millions of dollars simply because (invisibly) land value has skyrocketed and unnecessarily large lots of land are often legally required by local governments in their (also invisible) zoning codes. Take this bungalow now selling for over $2.6 million in California.

It’s understandable why elected officials seek the counsel of locals in places with housing issues. But if you want to know why the price of housing is so high, you have to talk to people present at the place and time the price is being set - that is, involved in the transactions - rather than simply people who have homes in the area.

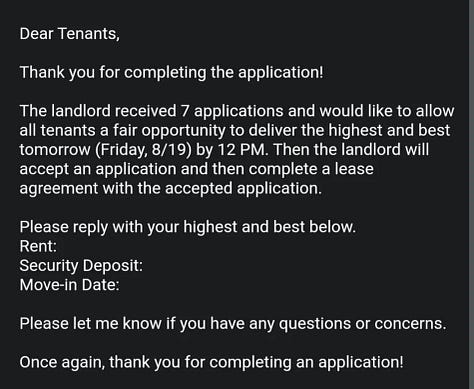

Behind the scenes, you see the same key dynamic: people who list properties getting tons of offers and prices increasing. Let’s revisit the viral vacant apartment in Brooklyn. Newsweek notes “bidding wars accounted for over 23 percent of lease signings in Brooklyn and about 16 percent of new lease signings in Queens…Fortune adds that bidding wars accounted for roughly one in five Manhattan lease signings in April, and, on average, landlords are "walking away with rents roughly 11 percent above the asking price."

Conclusion

Confusion over housing systems is normal for anyone—young, old, homeowner, renter, etc.

My hope is that understanding why the issue is hard to understand is the first step to explaining it better and broadening support for reform. Rather than cite abstract economic concepts to explain the shortage, try centering images that show them. After all, this isn’t an abstract problem of economics—it’s a problem of physically trying to fit a large number of people who want housing into a small number of available apartments.

When people can visualize that they are much more likely to support the clear solution—just build more apartments.

I've used the analogy before of the game of musical chairs. If you add one more chair, it's not the fastest kid who benefits the most, he would have gotten a seat regardless. It's the slowest kid that now gets a seat who wouldn't have without the extra chair, even if it's not the specific new chair you added.

As a former real estate agent, this is a very well done piece, congratulations.